With one month left until Nowruz, Baran fills a few plates and a large crystal wheat dish for the Haft-Sin table. She arranges them all in a row by her living room window. In April 2017, Baran left Iran for the last time. Nowruz 2023 is the sixth Eid that she celebrates in exile. She still does not know whether Nowruz 2024 will be in Turkey or a third country where she can build her permanent home.

Two months before Nowruz 2021, I met Baran. At that time, I had fled Iran for several months and was living in Istanbul on a one-year tourist visa; while waiting for the outcome of the court that was going on in Iran. I was spending my days with photography or in the quarantine of Covid-19 at home. Baran was introduced to me by a mutual friend. She and her roommates lived in a three bedroom apartment, which was like a piece of Iran to me. I remember the smell of Saffron and Iranian rice smelled until the entrance of the building. Whenever I would go to their apartment, It was the warm embrace of Baran, great Iranian homemade food, and the nights of gathering with friends and laughing at the pains of the days that passed.

I spent the first Nowruz in exile on the 2021 Nowruz at Baran’s house. The phones rang as soon as a few minutes passed after the Iranian new year started. Baran was swallowing her tears as she chatted with her sister Pegah; I was shedding my tears in Baran’s arms when my conversation with my family was over. Shortly after, Baran switched on the TV, and the sound of Googoosh, an old Iranian pop singer, full-filled the living room, and everybody danced with tears and laughter. They taught me the power of laughter through the pain—the ability to bear problems with the power of dance and hope.

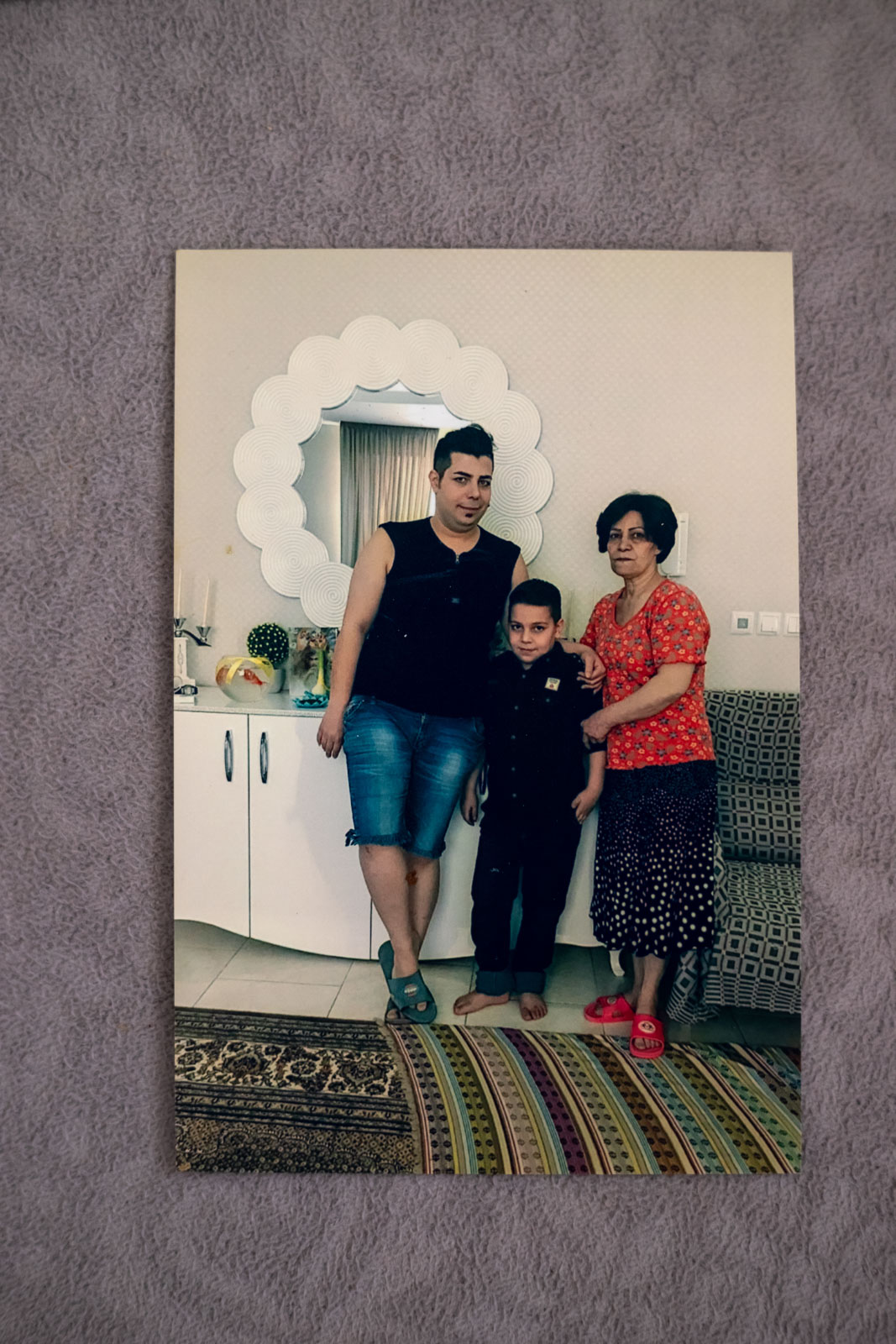

Baran has big dreams in her fourth decade of life. She is an Iranian refugee trans woman who studied political science before fleeing Iran. Baran, like most Iranian trans women, could not live her true gender identity freely due to social, legal, and Islamic problems. The police arrested her for wearing women’s clothes. So, she spent a horrible night in men’s police custody. According to the laws of the Islamic Republic, trans people are recognized with their true identity only when they go through the legal process of gender reassignment and submit to forced surgeries. According to Islamic laws governing the country of Iran, which are different from international laws, trans people are considered mentally ill. If they appear in society with a male ID card and female clothes, the police can arrest and imprison them on fraud charges. These bitter experiences made Baran hide her identity for many years and finally seek refuge in Turkey.

Turkey never gives passports to Iranian refugees but allows them to stay in predetermined cities when they go to a third country. This temporary stay may last for several years, and refugees never know when the exact time to settle in a third country will be. For this reason, they cannot plan for their future. After going to a third country, we Iranian refugees face the challenges of a new language, culture, laws, and customs in our residence. Baran has lived for six years in such a situation that I call the limbo of uncertainty. She is waiting for her visa and flight ticket to the United States, but she still plants her Nouruz’s greens, each for a friend who lives in the same town as her, just like every year habit of her mother.

Baran lost her mother due to illness a few years ago. Every year, she lights a candle next to the Haft-Sin table in memory of her mother. In which country would this table decorate Baran’s house next year?